Joins 🔗

Success

Joins are how we combine data from multiple tables. They're like the LOOKUP functions in Excel (but with some important differences)!

Note

The JOIN clause is optional. If you use it, it must come after the FROM clause and before the WHERE clause.

The JOIN clause combines data from tables

To get data from another table in Excel, you'd likely use one of the LOOKUP functions:

These functions keep your data in the same shape as the original table, but they pull in data from another table based on a common value.

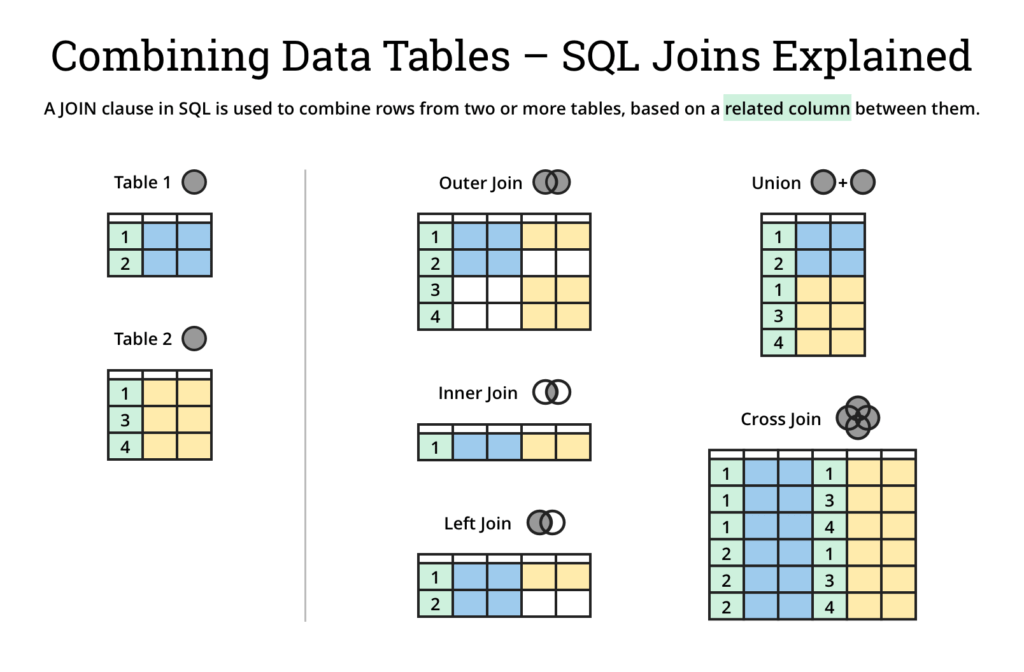

In SQL, we use the JOIN clause to do a similar thing. The JOIN clause is used to combine rows between tables based on a related column between them (usually).

In Microsoft SQL Server, there are a few different types of JOIN clauses:

We'll only cover the INNER JOIN and LEFT JOIN in this course, but you can find more information on the others in the official Microsoft documentation.

The JOIN syntax

To add a join to a query, you need to add the JOIN clause after the FROM clause and before the WHERE clause. We also need to tell SQL how these tables are related using the ON clause, for example:

SELECT *

FROM HumanResources.Employee

INNER JOIN HumanResources.vEmployeeDepartment

ON Employee.BusinessEntityID = vEmployeeDepartment.BusinessEntityID

;

This is a fairly intuitive example:

- The "base" table (in the

FROMclause) isHumanResources.Employeewhich has the employee information. - The "joined" table (in the

INNER JOINclause) isHumanResources.vEmployeeDepartmentwhich has the employee's current department. - The relationship between the two tables is that the

BusinessEntityIDin theEmployeetable matches theBusinessEntityIDin thevEmployeeDepartmenttable. This would be similar to theVLOOKUPfunction in Excel where theEmployee.BusinessEntityIDis the lookup value and thevEmployeeDepartment.BusinessEntityIDis the lookup column.

Notice how we've had to prefix the BusinessEntityID with the table name in the ON clause. This is because both tables have this column, so SQL needs us to prefix them to know which one we're referring to.

When we join tables, we don't usually want to SELECT * like we have above. Instead, we explicitly list the columns we want to see from each table:

SELECT

Employee.BusinessEntityID,

Employee.NationalIDNumber,

vEmployeeDepartment.FirstName,

vEmployeeDepartment.LastName,

vEmployeeDepartment.Department,

vEmployeeDepartment.JobTitle

FROM HumanResources.Employee

LEFT JOIN HumanResources.vEmployeeDepartment

ON Employee.BusinessEntityID = vEmployeeDepartment.BusinessEntityID

;

| BusinessEntityID | NationalIDNumber | FirstName | LastName | Department | JobTitle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 295847284 | Ken | Sánchez | Executive | Chief Executive Officer |

| 2 | 245797967 | Terri | Duffy | Engineering | Vice President of Engineering |

| 3 | 509647174 | Roberto | Tamburello | Engineering | Engineering Manager |

| 4 | 112457891 | Rob | Walters | Tool Design | Senior Tool Designer |

| 5 | 695256908 | Gail | Erickson | Engineering | Design Engineer |

Tip

Although you only need to prefix the columns that are ambiguous (exist in both tables), it's a good idea to prefix all columns in a query when there's a join. This makes it easier to read and understand the query, and it can help avoid errors if the tables change in the future.

We can alias/rename tables like we can with columns

When the table names are long, it can be helpful to give them a shorter name for the rest of the query. The way that we do this is identical to how we alias columns by using the AS keyword:

SELECT

Emp.BusinessEntityID,

Emp.NationalIDNumber,

Dep.FirstName,

Dep.LastName,

Dep.Department,

Dep.JobTitle

FROM HumanResources.Employee AS Emp

LEFT JOIN HumanResources.vEmployeeDepartment AS Dep

ON Emp.BusinessEntityID = Dep.BusinessEntityID

;

Tip

Although you can alias the tables to whatever you want, please try to make the alias meaningful. This makes the query easier to read and understand!

Step-by-step examples

We've just seen the LEFT JOIN clause in action, but let's break it down a bit more with some examples.

For these examples, we'll use the following fake tables:

Employee

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 |

| 2 | Bob | 1 |

| 3 | Charlie | 2 |

| 4 | Dave | 2 |

| 5 | Eve | 3 |

Department

| DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|

| 1 | Sales |

| 2 | Marketing |

Address

| EmployeeID | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Main Street | 2001-07-21 | 2002-10-30 |

| 2 | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 |

| 5 | 5 Log Lane | 2009-11-19 | 2020-03-15 |

| 5 | 6 Claw Close | 2023-03-16 | 2024-12-31 |

Employee LEFT JOIN Department

Suppose we write a query that LEFT JOINs the Department table onto the Employee table using the DepartmentID:

SELECT

Employee.EmployeeID,

Employee.EmployeeName,

Employee.DepartmentID,

Department.DepartmentName

FROM Employee

LEFT JOIN Department

ON Employee.DepartmentID = Department.DepartmentID

;

Since the Employee table is the "base" table (it's in the FROM clause), let's break down what's happening with each row in this table.

Employee 1

The first row is employee 1:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 |

We're joining the Department table to this on the DepartmentID column, specifically:

ON Employee.DepartmentID = Department.DepartmentID

This means that the information we get from the Department table will be where the DepartmentID in the Department table matches the DepartmentID in the Employee table which, in this case, is 1:

| DepartmentID | DepartmentName | |

|---|---|---|

| → | 1 | Sales |

| 2 | Marketing |

That means that we take the Sales value from this table for the first row of the Employee table:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 | Sales |

This is just like a lookup in Excel!

Employee 2

The second row is employee 2:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Bob | 1 |

Bob has the same DepartmentID as Alice, so the steps for Bob are the same as they were for Alice -- we get the Sales value from the Department table:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Bob | 1 | Sales |

Employee 3

The third row is employee 3:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | Charlie | 2 |

This time, the DepartmentID is 2:

| DepartmentID | DepartmentName | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sales | |

| → | 2 | Marketing |

Therefore, we get the Marketing value from the Department table for Charlie:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Charlie | 2 | Marketing |

Employee 4

The fourth row is employee 4:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | Dave | 2 |

Dave also has a DepartmentID of 2, so we take the Marketing value from the Department table for Dave:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Dave | 2 | Marketing |

Employee 5

The fifth row is employee 5:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Eve | 3 |

This is an interesting case. Eve has a DepartmentID of 3, but there's no DepartmentID of 3 in the Department table:

| DepartmentID | DepartmentName | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sales | |

| 2 | Marketing |

This means that we can't find a DepartmentName for Eve, so we instead get a NULL value for the DepartmentName:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Eve | 3 | NULL |

Putting it all together

When we put all of these rows together, we get the following result:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 | Sales |

| 2 | Bob | 1 | Sales |

| 3 | Charlie | 2 | Marketing |

| 4 | Dave | 2 | Marketing |

| 5 | Eve | 3 | null |

This is how the LEFT JOIN clause works -- it grabs whatever data it can from the "joined" table and fills in NULL values where it can't find a match.

Employee INNER JOIN Department

Now let's look at the INNER JOIN clause. We'll use the exact same query as the last example, but we'll change the LEFT JOIN to an INNER JOIN:

SELECT

Employee.EmployeeID,

Employee.EmployeeName,

Employee.DepartmentID,

Department.DepartmentName

FROM Employee

INNER JOIN Department

ON Employee.DepartmentID = Department.DepartmentID

;

We could find a match for the first four rows, so they are the same as they were in the LEFT JOIN example:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 | Sales |

| 2 | Bob | 1 | Sales |

| 3 | Charlie | 2 | Marketing |

| 4 | Dave | 2 | Marketing |

However, what happens with employee 5 is different: an INNER JOIN only keeps rows where there's a match!

Since there's no match for employee 5 in the Department table, we don't get a row for Eve at all! This means that the result of the INNER JOIN is:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 | Sales |

| 2 | Bob | 1 | Sales |

| 3 | Charlie | 2 | Marketing |

| 4 | Dave | 2 | Marketing |

This is the main difference between the LEFT JOIN and the INNER JOIN clauses and is what catches a lot of people out when they're new to SQL.

Tip

If you're not sure which join type to use, it's usually best to start with a LEFT JOIN and then change it to an INNER JOIN when you're comfortable that you're not missing any data.

Employee LEFT JOIN Address

This time, suppose we write a query that LEFT JOINs the Address table onto the Employee table using the EmployeeID:

SELECT

Employee.EmployeeID,

Employee.EmployeeName,

Address.Address,

Address.FromDate,

Address.ToDate

FROM Employee

LEFT JOIN Address

ON Employee.EmployeeID = Address.EmployeeID

;

As with the last example, we'll break down what's happening with each row in the Employee table. We'll ignore the DepartmentID column in the Employee since we're not using it in the query.

Employee 1

The first row is employee 1:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName |

|---|---|

| 1 | Alice |

This time, we're joining the Address table to this on the EmployeeID column, specifically:

ON Employee.EmployeeID = Address.EmployeeID

This means that the information we get from the Address table will be where the EmployeeID in the Address table matches the EmployeeID in the Employee table which, in this case, is 1:

| EmployeeID | Address | FromDate | ToDate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| → | 1 | 1 Main Street | 2001-07-21 | 2002-10-30 |

| 2 | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 | |

| 5 | 5 Log Lane | 2009-11-19 | 2020-03-15 | |

| 5 | 6 Claw Close | 2023-03-16 | 2024-12-31 |

That means that we take the 1 Main Street address (plus the dates) from this table for the first row of the Employee table:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 Main Street | 2001-07-21 | 2002-10-30 |

Employee 2

The second row is employee 2:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName |

|---|---|

| 2 | Bob |

Bob's EmployeeID is 2, so we look for the address in the Address table where the EmployeeID is 2:

| EmployeeID | Address | FromDate | ToDate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Main Street | 2001-07-21 | 2002-10-30 | |

| → | 2 | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 |

| 5 | 5 Log Lane | 2009-11-19 | 2020-03-15 | |

| 5 | 6 Claw Close | 2023-03-16 | 2024-12-31 |

This means that we get the 2 Rocky Road address (plus the dates) from the Address table for Bob:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Bob | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 |

Employee 3

The third row is employee 3:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName |

|---|---|

| 3 | Charlie |

Charlie's EmployeeID is 3, so we look for the address in the Address table where the EmployeeID is 3:

| EmployeeID | Address | FromDate | ToDate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Main Street | 2001-07-21 | 2002-10-30 | |

| 2 | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 | |

| 5 | 5 Log Lane | 2009-11-19 | 2020-03-15 | |

| 5 | 6 Claw Close | 2023-03-16 | 2024-12-31 |

Since we can't find a match for Charlie and we're using a LEFT JOIN, we'll get NULL values for the Address columns:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Charlie | null | null | null |

Employee 4

The fourth row is employee 4:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName |

|---|---|

| 4 | Dave |

Dave's EmployeeID is 4 which also doesn't have a match in the Address table, so we get NULL values for the Address columns:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Dave | null | null | null |

Employee 5

The fifth row is employee 5:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName |

|---|---|

| 5 | Eve |

Eve's EmployeeID is 5, and they have two addresses in the Address table:

| EmployeeID | Address | FromDate | ToDate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Main Street | 2001-07-21 | 2002-10-30 | |

| 2 | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 | |

| → | 5 | 5 Log Lane | 2009-11-19 | 2020-03-15 |

| → | 5 | 6 Claw Close | 2023-03-16 | 2024-12-31 |

This is another place where SQL is different to Excel. Since we have two matches for Eve in the Address table, we get two rows in the result -- we keep both!

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Eve | 5 Log Lane | 2009-11-19 | 2020-03-15 |

| 5 | Eve | 6 Claw Close | 2023-03-16 | 2024-12-31 |

Putting it all together

When we put all of these rows together, we get the following result:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 Main Street | 2001-07-21 | 2002-10-30 |

| 2 | Bob | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 |

| 3 | Charlie | null | null | null |

| 4 | Dave | null | null | null |

| 5 | Eve | 5 Log Lane | 2009-11-19 | 2020-03-15 |

| 5 | Eve | 6 Claw Close | 2023-03-16 | 2024-12-31 |

Warning

In Excel, you'd only get one row for Eve (Excel would just keep the first match), but in SQL you get all the matches. This is a common source of confusion for people new to SQL.

However, this behaviour is super useful when used correctly! Just keep an eye out for it.

Employee INNER JOIN Address

To finish off, let's consider the same query but with an INNER JOIN instead of a LEFT JOIN:

SELECT

Employee.EmployeeID,

Employee.EmployeeName,

Address.Address,

Address.FromDate,

Address.ToDate

FROM Employee

INNER JOIN Address

ON Employee.EmployeeID = Address.EmployeeID

;

Can you guess what the result will be?

It's the same as the LEFT JOIN example, but without rows for Charlie and Dave since they don't have a match in the Address table using this condition:

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 Main Street | 2001-07-21 | 2002-10-30 |

| 2 | Bob | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 |

| 5 | Eve | 5 Log Lane | 2009-11-19 | 2020-03-15 |

| 5 | Eve | 6 Claw Close | 2023-03-16 | 2024-12-31 |

LEFT JOIN is probably the most common join type

Since the INNER JOIN will drop rows that don't have a match in the "joined" table, it's usually "safer" to use LEFT JOIN to make sure that you don't accidentally lose any data during the join.

This is common practice (favouring LEFT over INNER), so you'll often see people use LEFT JOIN unless they have a specific reason to use a different type.

INNER JOIN is the default join type

If you don't specify LEFT or INNER (or any of the others), then SQL will default to an INNER JOIN:

SELECT

Employee.EmployeeID,

Employee.EmployeeName,

Employee.DepartmentID,

Department.DepartmentName

FROM Employee

JOIN Department /* This will be an `INNER JOIN` */

ON Employee.DepartmentID = Department.DepartmentID

;

Although this is the default, it's always a good idea to be explicit about the join type you're using. This makes the query easier to read and understand, and it can help avoid errors if the tables change in the future.

There can be several joins in a single query

The examples above have just been joining two tables, but you can join as many tables as you like in a single query.

For example, we could combine the Employee, Department, and Address tables in a single query:

SELECT

Employee.EmployeeID,

Employee.EmployeeName,

Employee.DepartmentID,

Department.DepartmentName,

Address.Address,

Address.FromDate,

Address.ToDate

FROM Employee

LEFT JOIN Department

ON Employee.DepartmentID = Department.DepartmentID

LEFT JOIN Address

ON Employee.EmployeeID = Address.EmployeeID

;

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID | DepartmentName | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 | Sales | 1 Main Street | 2001-07-21 | 2002-10-30 |

| 2 | Bob | 1 | Sales | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 |

| 3 | Charlie | 2 | Marketing | null | null | null |

| 4 | Dave | 2 | Marketing | null | null | null |

| 5 | Eve | 3 | null | 5 Log Lane | 2009-11-19 | 2020-03-15 |

| 5 | Eve | 3 | null | 6 Claw Close | 2020-03-16 | 2024-12-31 |

Notice how, although the Employee table only has five rows, we've ended up with six because of the (LEFT) join with the Address table.

Similarly, can you guess what the output would be if we used INNER JOINs instead of LEFT JOINs?

SELECT

Employee.EmployeeID,

Employee.EmployeeName,

Employee.DepartmentID,

Department.DepartmentName,

Address.Address,

Address.FromDate,

Address.ToDate

FROM Employee

INNER JOIN Department

ON Employee.DepartmentID = Department.DepartmentID

INNER JOIN Address

ON Employee.EmployeeID = Address.EmployeeID

;

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | DepartmentID | DepartmentName | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 1 | Sales | 1 Main Street | 2001-07-21 | 2002-10-30 |

| 2 | Bob | 1 | Sales | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 |

We'd only get two rows! We'd lose the rows for Charlie and Dave in the join with the Address table, and we'd lose the row(s) for Eve in the join with the Department table.

Info

You can use whichever join types you want for each join, there's no need to use all the same (e.g. all LEFT join).

Other tips and tricks

The examples above are "typical" examples of joins, but you'll find that you can use joins in a lot of different ways!

You can use any condition in a join

We've just been using the = operator in the ON clause, but you can use any condition you like (and as many as you want!).

For example, we could also filter on the dates in the Address table when we join it to the Employee table:

SELECT

Employee.EmployeeID,

Employee.EmployeeName,

Address.Address,

Address.FromDate,

Address.ToDate

FROM Employee

INNER JOIN Address

ON Employee.EmployeeID = Address.EmployeeID

AND Address.FromDate >= '2010-01-01'

;

| EmployeeID | EmployeeName | Address | FromDate | ToDate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Bob | 2 Rocky Road | 2012-07-04 | 2018-02-11 |

| 5 | Eve | 6 Claw Close | 2020-03-16 | 2024-12-31 |

Tables can be joined to themselves

There's nothing stopping you from joining a table to itself! This can be useful when you want to compare rows within the same table, but this is pretty rare, so we won't cover it in this course.

The SQL for running these examples

Error

The data for these examples isn't in the AdventureWorks database that we're using, so it has been created for this section. If you want to run these examples yourself, you can adjust the SQL below. Note that this is using some features that we haven't covered yet!

For the examples above, the rows are created on the fly. You're not expected to understand this yet, but it's provided so that you can run the SQL yourself if you want to.

WITH

Employee AS (

SELECT *

FROM (

VALUES

(1, 'Alice', 1),

(2, 'Bob', 1),

(3, 'Charlie', 2),

(4, 'Dave', 2),

(5, 'Eve', 3)

) AS V(EmployeeID, EmployeeName, DepartmentID)

),

Department AS (

SELECT *

FROM (

VALUES

(1, 'Sales'),

(2, 'Marketing')

) AS V(DepartmentID, DepartmentName)

),

Address AS (

SELECT *

FROM (

VALUES

(1, '1 Main Street', '2001-07-21', '2002-10-30'),

(2, '2 Rocky Road', '2012-07-04', '2018-02-11'),

(5, '5 Log Lane', '2009-11-19', '2020-03-15'),

(5, '6 Claw Close', '2020-03-16', '2024-12-31')

) AS V(EmployeeID, Address, FromDate, ToDate)

)

/* Edit this part */

SELECT

Employee.EmployeeID,

Employee.EmployeeName,

Employee.DepartmentID,

Department.DepartmentName,

Address.Address,

Address.FromDate,

Address.ToDate

FROM Employee

INNER JOIN Department

ON Employee.DepartmentID = Department.DepartmentID

INNER JOIN Address

ON Employee.EmployeeID = Address.EmployeeID

;

Further reading

Check out the official Microsoft documentation for more information on the JOIN clause at:

The video version of this content is also available at:

Additional join modifiers in other SQL flavours

Microsoft SQL Server has a fairly limited number of join features, but other SQL flavours add loads of additional modifiers to the JOIN clause.

If you see something that you don't recognise, make sure that you search for it in the documentation for the specific SQL flavour that you see the thing in!

Visual representation of joins

If you're a visual learner, you might find it helpful to read the following article from Atlassian (the company behind Jira and Confluence) which has some great visual representations of the different join types:

For example, their "cheat sheet" is: